Alexis Lapointe, a.k.a. Alexis le Trotteur (1860-1924): the Man, the Legend

par Gauthier, Serge

Alexis Lapointe, known as "LeTrotteur", "le Cheval du Nord," the "Surcheval," and the "Centaur", was the subject of both admiration and mockery in his day. Over the course of his lifetime, he remained a simple labourer, an odd man whose tomfoolery brought joy to those around him. In death, however, he became a mythical figure, a legendary athlete the likes of which he himself would never have imagined. And what can be said about the exhumation of his remains from a cemetery in La Malbaie in November 1966, 42 years after his death? What about the exhibition of his skeleton in museums throughout the Saguenay for 35 years? This poor fellow seems to have become more famous in death than in his life.

Article disponible en français : Alexis Lapointe dit le Trotteur (1860-1924) : l’homme et sa légende

A Thriving Legacy

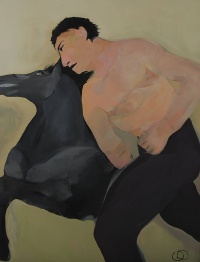

At least two songs – "Train de vie," by Mes Aïeux and "Alexis le Trotteur", by Charlevoix singer Jean-Yves Belley – have been written about Alexis Le Trotteur. A street in Quebec City, a bridge and an endowment fund in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region and even a day-care center (CPE) in Montreal all bear his name as well. A comic strip published in Vidéo-Presse magazine in the 1970s told tales of his exploits with a splash of humour. Around the same time, Montreal's Compagnie de danse Eddy Toussaint devoted a ballet to him. Les Échassiers de Baie-Saint-Paul - a circus troupe predating the Cirque du Soleil - put on a show in his honour in 1980. He has been immortalised in works of art by artists such as Claude Le Sauteur and Johanne O'Donnell (for the Musée Régional Laure-Conan in La Malbaie in 1981). A cartoon starring the legendary figure was recently created, and a number of Quebec storytellers, in particular Jocelyn Bérubé, tell stories about him and his amazing feats. Dozens of authors, such as folklorist Marius Barbeau (1883-1969), have also written about his escapades. There is even talk of a full-length Alexis Le Trotteur movie. All that might seem like an awful lot of attention for an eccentric man born in a small, mid-19th-century Charlevoix town, but it seems as though no one could have predicted the fabulous destiny of the man known as "Le Trotteur."

The Life of Alexis le Trotteur

The legendary "Trotteur" led alife that was in all appearance rather ordinary, though not completely devoid of interest. Alexis Lapointe was born near Chute Nairne in La Malbaie (now known as Clermont) on June 4th, 1860, the eighth of fourteen children. Despite what many people, including his biographer Jean-Claude Larouche, may think, Lapointe did not exactly have a modest upbringing; in fact, his family was rather well off for the times. His mother, Adelphine Tremblay, was the daughter of Alexis Tremblay (Picoté), a well-known La Malbaie businessman who, as one of the founders of the Société des vingt-et-un in 1837, was a key figure in the settlement of the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region. His father, François Lapointe, came from a family that owned a great deal of land and stood out as one of the wealthiest in the area. Of course, all of this is relative: no one was terribly rich in Charlevoix at the time. Nonetheless, Le Trotteur's origins are far from the most humble.

Baptised at home, fearing that he would not survive to be taken to the church baptistry, Alexis Lapointe's health as a newborn was rather poor. Later, throughout his childhood and adolescence, it was his mental health that seemed most fragile. As a young child, he would build wooden horses to play with and then whinny and imitate the animal. His strange behaviour bothered his family, who felt embarrassed by him. Lapointe did not attend school very long, and therefore had little education; he had limited reading ability, but could not write and could only barely count. Growing up, he took to wandering the countryside pretending he was a horse, and so legends and stories of him began to spread in the places he frequented, namely Charlevoix, the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region and the Matapedia Valley. He only had one steady job in his life - building bake ovens of which he built more than 200.

Alexis Lapointe never married, though he did love women. He was a tireless dancer, an incredible jumper and along-time player of "big double harmonicas." His claim to fame, however, was his running ability. He raced regularly against trotting horses, sometimes against dogs and cows, and also against automobiles, boats, and of course, trains. As a matter of fact, he died in Alma in 1924 when he was crushed by a train car. Could he have been running in front of it? According to Marius Barbeau, such stories border on the absurd; his death was simply the result of an unfortunate accident. At the time of his death, Lapointe was working as a labourer in the construction of a dam. He was 64, and until that moment, had lived a rather ordinary life. His body was brought back to Charlevoix and buried in a common grave, and he was all but forgotten. It wasn't until after his death that his legend grew and took its place in popular culture.

The Three Variations on the Legend of Le Trotteur

Research (NOTE 1) reveals three versions of the legend of Alexis Lapointe. The first, which dates back to the mid-19th century, depicts him as a showman. (NOTE 2) A second view, based on Marius Barbeau's interpretation of local folklore, paints a portrait of a legendary runner. The third interpretation of this historic figure came about after his body was exhumed by researcher Jean-Claude Larouche and reinforces the image of Le Trotteur as a true athlete. Let us look at the origins and characteristics of each of these views.

The story of Alexis Lapointe the showman is the oldest and its origins can be traced to the oral history of Charlevoix and, to a lesser degree, the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region. During his lifetime, Le Trotteur was seen as a sort of entertainer; it was his showmanship that attracted the most attention. In his book Au temps de Benoît XV, (NOTE 3) Lapointe's contemporary Ernest Bilodeau (1881-1956) writes of spectators paying Le Trotteur to show off his running abilities. More often than not, these demonstrations ended with Lapointe being mocked or derided, without anyone really caring about his performance or the absurdity of a slow-wittedman racing against a horse. Because of this, Alexis Le Trotteur was well liked by his contemporaries, but was also sometimes misled or mistreated, as evidenced by certain oral traditions. (NOTE 4) Lapointe's showmanship didn't bring him much in terms of financial gains either; he remained poor his entire life and died in 1924 in a state of near-destitution, forced to earn a living as a labourer despite his age. He was buried in a common grave and his passing was treated with general in difference by the community. In the end, his reputation as an entertainer meant little to his peers.

The second version of the legend, this time of Alexis Lapointe as a world-class runner, comes mainly from literature. A chapter of folklorist Marius Barbeau's 1936 book The Kingdom of Saguenay (NOTE 5) was devoted entirely to Le Trotteur. Barbeau's description was based on research he carried out on Charlevoix folklore in 1916, but he never actually met Le Trotteur himself. His story, "Alexis the Runner," is not a report on his field research, but rather a fictional tale based on local folklore. In fact, Barbeau lends no credence to accounts of Le Trotteur's buffoonery. Nonetheless, thanks to the Canada Steamship Lines and its Saguenay cruises, the book was widely circulated and became very popular among its target audience, the company's primarily English-speaking clientele. "Alexis the Runner" was translated into French for a number of periodicals and popular newspapers and it also appeared in Le Saguenay légendaire. (NOTE 6) The legend of the mythical runner grew in popularity and spread throughout Quebec and Canada, and while the tale of Le Trotteur being killed while racing against a train was largely the product of Marius Barbeau's imagination, it nonetheless became the most widely believed story of his death. However, Alexis Le Trotteur was yet to be considered an athlete.

Alexis Le Trotteur the athlete is in fact a much more recent version of the legend. It wasn't until researcher Jean-Claude Larouche began looking into the legend in 1966 that anyone thought of Alexis Lapointe as a man capable of exceptional feats of athleticism. Larouche, a physical education student at the University of Ottawa, wrote his thesis on Alexis Le Trotteur and his legendary exploits. Starting with the idea that there may have been a scientific explanation for his physical prowess, Larouche decided to exhume Lapointe's remains in order to study them. The exhumation, which took place at the La Malbaie cemetery in November 1966, was complicated by the fact that Lapointe had been buried without a tombstone in a common grave. Nonetheless, Larouche carried out his study and published his biographical and scientific report on Alexis Le Trotteur in 1971. (NOTE 7) His conclusions support the theory that Le Trotteur possessed the characteristics of a born athlete, results which were well received and firmly established Alexis Le Trotteur's legacy as a true athlete. Naturally, this view fit in very nicely with the jogging trend that swept a younger, freer and more physically active generation of Quebeckers in the 1960s and 1970s. Presenting Alexis Le Trotteur as an athlete was also away of revamping and updating the original legend, which didn't emphasize his exceptional physical abilities. In 1975, Jean-Claude Larouche donated Alexis Le Trotteur's skeleton to the Musée du Saguenay. The bones were displayed there for more than thirty years before being moved to the Musée de la Pulperie de Saguenay, where they were still found in 2008.

A Strange Way to Commemorate the Legend and the Man

The fact that Alexis Lapointe's skeleton was put on display soon raised a number of questions that echoed throughout the public sphere. On May 13th and 14th, 2006, an article by journalist and historian Jean-François Nadeau on the exhibitionand the conditions surrounding Lapointe's exhumation appeared on the front page of Montreal daily newspaper Le Devoir. Around the same time, the Société d'Histoire de Charlevoix began demanding that Alexis Lapointe be laid to rest in his native Charlevoix. The debate continued in 2008, but a settlement seems imminent, as management of the Musée de la Pulperie de Saguenay is now considering the idea of allowing Le Trotteur's remains to be buried. In any case, the debate just goes to show the continued interest - even in death -in the famous Trotteur.

In fact, the legend of Alexis "Le Trotteur" Lapointe is even more alive after his death than it ever was during his lifetime. Isn't it time to lay to rest his remains and his legend, lest they return to haunt us in the form of another, as-of-yet-unknown identity? Now that we have publicly celebrated the legendary athlete that was Alexis LeTrotteur, shouldn't we let him rest? The debate is ongoing, and the legend lives on...

Serge Gauthier, Ph.D.

Ethnologist and historian

Researcher at the Centre de Recherche sur l'Histoire et le Patrimoine de Charlevoix

NOTES

Note 1. See the special issue devoted to Alexis le Trotteur in Revue d'histoire de Charlevoix, number 60 (September, 2008), 20 pages.

Note 2. Serge Gauthier, L'homme-spectacle, La Malbaie, Musée régional Laure-Conan, 1981, 16 pages.

Note 3. Ernest Bilodeau, Au tempsde Benoît XV, Montréal, Imprimerie de la Salle, 1923, p. 10-12.

Note 4. Léo Simard, La petite histoire de Charlevoix, La Malbaie, n. ed., 1987, 304 pages

Note 5. Marius Barbeau, The Kingdom of Saguenay, Toronto, Mc Millan, 1936, p. 153-167.

Note 6. Marius Barbeau, Le Saguenay légendaire, Montréal, Beauchemin, 1967, p. 88-105

Note 7. Jean-Claude Larouche, Alexisle Trotteur, Montréal, Éditions du Jour, 1971, 297 pages

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Alexis Lapointe dit L

Alexis Lapointe dit L

e Trotteur (186... -

Alexis Lapointe dit l

Alexis Lapointe dit l

e Trotteur, ver... -

Alexis le Trotteur co

Alexis le Trotteur co

ntre Baba (1981... -

Alexis le Trotteur co

Alexis le Trotteur co

ntre le cheval ...

-

Alexis le Trotteur, 1

Alexis le Trotteur, 1

967 Squelette d'Alexis le

Squelette d'Alexis le

Trotteur au Mu...Documents PDF

-

Décès d'Alexis Lapointe dit le Trotteur

Décès d'Alexis Lapointe dit le Trotteur

-

Extrait du roman Le Cheval du Nord de Marjolaine Bouchard (Éditions JCL, 1999)

Extrait du roman Le Cheval du Nord de Marjolaine Bouchard (Éditions JCL, 1999)

-

Paroles de la chanson « Train de vie (le Surcheval) » du groupe québécois Mes Aïeux

Paroles de la chanson « Train de vie (le Surcheval) » du groupe québécois Mes Aïeux

Hyperliens

- LAPOINTE, ALEXIS, known as Alexis le Trotteur (Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online)

- Entrevue de Serge Gauthier à l'émission télévisée C'est ça la vie (Radio-Canada, vendredi 10 octobre 2008) concernant la remise en terre des ossements d'Alexis le Trotteur (French only)

- Société historique de Charlevoix (French only)

Catégories

© All rights reserved, 2007

Encylcopedia of French Cultural

Heritage in North America